My memories of watching the Tour de France are a blur, and the names of most riders have faded in the hazy corners of my mind. But there are a few famous (or infamous) names that I won’t easily forget: Froome, Armstrong, Ullrich, Pantani, LeMond… Oh, and one more: Mavic.

That’s right, I’m not talking about a rider, I’m thinking of the prolific French wheel manufacturer. At over 130 years old, Mavic is a core part of bike racing history and is older than the Tour de France. For nearly 50 years, Mavic’s yellow neutral service cars and motos followed the peloton, loaded up with wheels and matching yellow bikes. I’ll never forget those bright yellow cars, zipping through the French countryside, saving stranded riders, even if those riders' names escape me.

That’s right, I’m not talking about a rider, I’m thinking of the prolific French wheel manufacturer. At over 130 years old, Mavic is a core part of bike racing history and is older than the Tour de France. For nearly 50 years, Mavic’s yellow neutral service cars and motos followed the peloton, loaded up with wheels and matching yellow bikes. I’ll never forget those bright yellow cars, zipping through the French countryside, saving stranded riders, even if those riders' names escape me.

Sadly, it was announced earlier this year that neutral service at the Tour will be taken over by Shimano. It’s the end of an era. But Mavic’s legacy is much bigger than a fleet of yellow cars and motorcycles.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Mavic. The first bike upgrade I ever purchased was a set of Mavic Ksyrium Elites. Fifteen years later, I ride a set of Ksyrium Pro Carbon SLs, and there have been countless Mavic road and mountain bike wheels in between. To honor this iconic brand, I decided to take a ride down memory lane. Mavic’s history is the history of cycling, and you may be surprised to learn how much its innovative ideas and designs have shaped the sport into what it is today.

Contents

- The beginning

- The breakthrough

- Wheel innovations

- The dawn of wheel systems

- The age of aero

- A shift in performance

- Mavic and the mountain bike

- The race saviors

The beginning: Pedal cars and mudguards

Clockwise: The original Mavic logo, the original factory in Lyon, France, apron mudguard advertisement, children's pedal car.

Clockwise: The original Mavic logo, the original factory in Lyon, France, apron mudguard advertisement, children's pedal car.

Mavic was founded in 1889 by Charles Idoux and Lucien Chanel in Lyon, France to provide spare parts for the growing bicycle market. The name “Mavic” is actually an acronym which stands for “Manufacture d’Articles Vélocipédiques Idoux et Chanel,” which roughly translates to “Idoux and Chanel’s Manufactory of Articles for Velocipedes.”

What’s a velocipede you ask? Well, Mavic is so old that the bicycle as we know it today, the “safety bicycle,” had only just been invented. The word “bicycle” hadn’t even entered most people’s vocabulary. Instead, the term “velocipede” described any human-powered land vehicle with one or more wheels. It was first coined as a French name for the Laufmaschine (which some might know as a “dandy horse”) that was first developed in 1817.

Mavic first specialized in manufacturing wooden bicycle rims and other small components. In the 1930s, Mavic expanded its manufacturing capabilities to make toy pedal cars for children, outfitted with spoked wheels, decorative hub-cabs, a chain drive to the back axle, and even a working hood and trunk.

The company’s crown jewel, however, was the 1934 “apron mudguard.” Mavic took the standard mudguard design and added a flexible rubber apron to the trailing edge to deflect water and mud away from riders’ shoes. Today, countless bike commuters still benefit from this nearly 90-year-old Mavic invention.

The breakthrough: Dura alloy rims

In 1934, cycling was an established sport experiencing huge growth. But bike technology hadn't caught up with the times. Riders were still limited to fixed-gear bikes that rolled on wooden rims. These rims usually weighed a hefty 1,200 grams. Many modern rims are 300-500 grams.

With some experience in metal extrusion, Mavic began experimenting with various alloys to produce rims. It ended up creating the Dura rim, made out of Duralumin, an alloy of copper and aluminum. This breakthrough allowed Mavic to make rims that weighed only 750 grams.

With some experience in metal extrusion, Mavic began experimenting with various alloys to produce rims. It ended up creating the Dura rim, made out of Duralumin, an alloy of copper and aluminum. This breakthrough allowed Mavic to make rims that weighed only 750 grams.

The new rim was also the first to be constructed with eyelets. Eyelets spread the stress of the spokes between the lower and upper walls of the rim, allowing the rim to use a lighter, hollow design. Interestingly, a solo Italian designer, Mario Longhi, had the same idea and managed to register his patent two hours before Mavic could. Fortunately, Longhi allowed Mavic to exploit the design under license.

When the Dura rim came out in 1934, metal rims were banned by the rules of the Tour de France. Because of this, the new rim had to be tested secretly. 1931 Tour de France winner, Antonin Magne, rode a set that was painted to look like normal wooden rims so they wouldn’t attract attention.

Magne used the rims to take the yellow jersey on the second stage of the 1934 Tour. He won two more stages along the way, including the Tour’s first-ever individual time trial, and won the yellow jersey with a 27-minute lead. The next year, the rules changed, and in 1935, all racers in the Tour were riding on Dura rims. For the next 60 years, alloy rims would dominate professional cycling.

Wheel innovations: Clinchers, UST tubeless, and carbon

Decades later, Mavic continued to innovate with its aluminum rim designs. In 1975, it was the first to anodize alloy rims which improved rim wall hardness and prevented corrosion. That same year, it introduced the Module E hooked rim. This rim was designed specifically to work with the Michelin Elan, the first widely available high-pressure clincher tire.

Decades later, Mavic continued to innovate with its aluminum rim designs. In 1975, it was the first to anodize alloy rims which improved rim wall hardness and prevented corrosion. That same year, it introduced the Module E hooked rim. This rim was designed specifically to work with the Michelin Elan, the first widely available high-pressure clincher tire.

When inflating the Elan tire above 90psi, riders had issues with tubes blowing the bead off of other rims. The Module E solved this issue with hooked beads that kept the tire seated. This new design set the standard for modern clincher wheels and enabled the development of modern, high-pressure clincher tires.

In the last decade, tubeless wheels and tires have become commonplace. But Mavic was already working on the technology in the late-’90s. It collaborated with Michelin and Hutchinson, the world’s two largest tire manufacturers, to create the Crossmax UST tubeless rim in 1999.

The profile of Mavic's UST mountain and road rims.

The profile of Mavic's UST mountain and road rims.

UST stands for Universal System Tubeless, and it is a technology patented by Mavic. A UST rim and tire are manufactured to specific tolerances. A UST tire bead is square-shaped and the tire casing has a butyl liner to make it 100% airtight. A UST rim has a matching well for the tire bead to seat and generally has no exposed spoke nipples. This means a UST tubeless set-up doesn’t require any additional tape or sealant to hold air pressure (though sealant can be used). Tubeless systems had long been the standard for cars and motorcycles. UST successfully brought that technology to bicycles.

Currently, “tubeless-ready” systems are now more popular because they’re simpler to manufacture. Tolerances don’t have to be as precise because sealant can compensate, and in many cases, the tires are lighter because they don’t use a fully airtight casing. Fortunately, Mavic’s UST rims are compatible with both UST and tubeless-ready tires.

And then there’s carbon. By the early ‘00s, it was clear that carbon fiber rims were the next big thing. Mavic already had ample experience building carbon disc wheels (more on that later) and began developing prototype carbon road wheels with the American Garmin-Barracuda team, including prototype M40 carbon rims for Paris-Roubaix.

Zipp managed to beat Mavic to the punch by winning Roubaix with Fabian Cancellara in 2010, but not everyone was convinced, and the "Hell of the North" was still dominated by hand-built alloy wheels. In the 2011 edition, Garmin-Barracuda rider, Johan Vansummeren, rode Roubaix on carbon wheels for the first time. He later commented that the difference in weight and improved aerodynamics gave him a noticeable advantage on paved sectors.

Vansummeren became the second man to win Paris-Roubaix on carbon wheels, and their durability was proven when Vansummeren rode the last three miles with a flat tire to hold off a charging Cancellara. Cancellara’s 2010 win showed that winning on carbon was possible, but Vansummeren’s 2011 win proved carbon was the future. Now, you won’t find a single alloy rim in the pro peloton.

The dawn of wheel systems: Cosmic, Helium, and Ksyrium

Up until the mid-’90s, buying a wheel meant choosing a separate hub, spokes, and rim. If you lacked wheel-building skills, then you also needed to find someone who could lace it all together. Mavic decided to change the status quo by offering pre-built, complete wheelsets that it called “wheel systems.”

French competitor, Roval, had experimented with complete wheel systems a few years earlier, but it was the Mavic Cosmic, released in 1994, that was the first widely available pre-built wheel. The cycling public was unaccustomed to the concept at the time, so the revolutionary Cosmic saw lackluster sales and garnered little attention.

That all changed in 1996, however, when Mavic launched the Helium, an ultra-light wheelset designed for mountain stages. The Helium wheelset weighed 1,650 grams. This is pretty unremarkable by today’s standards, but at the time it was feathery light, and they quickly became the climber's wheels of choice. This weight was possible because Mavic was able to design all of the wheel components together as a complete, optimized system.

That all changed in 1996, however, when Mavic launched the Helium, an ultra-light wheelset designed for mountain stages. The Helium wheelset weighed 1,650 grams. This is pretty unremarkable by today’s standards, but at the time it was feathery light, and they quickly became the climber's wheels of choice. This weight was possible because Mavic was able to design all of the wheel components together as a complete, optimized system.

Cycling fans will likely remember the Helium-equipped carbon Look ridden by Laurent Jalabert in the Tour. The red anodized rims and hubs stood out and quickly became iconic. And because the wheels were sold as a complete, pre-built wheelset, everyday riders were able to get their hands on the exact same wheels that the King of the Mountains was riding.

The Helium’s success led to Mavic’s Ksyrium wheel in 2000, which improved on the Helium wheel by introducing stiffer, oversized aluminum spokes. Because the Ksyrium was a wheel system, Mavic engineers could design the entire hub and a rim around these new spokes, using lower spoke counts and new rim drilling methods to create a wheel that was similar in weight but much stiffer. Lance Armstrong famously used a pair of prototype Ksyriums to “win” his first Tour de France in 1999.

Mavic’s move to pre-built wheels was risky. Bike shops profited from the hefty labor margins from building wheels, so Mavic was a threat to their businesses. For many years, some shops refused to stock Mavic wheels. But eventually, the convenience of purchasing a complete, ready-to-ride wheelset won over most riders. Though there are still hand-built wheel aficionados out there, pre-built wheels now dominate the market.

The age of aero: Comete carbon disc wheel

In the 1970s, Mavic engineers developed an interest in aerodynamics after seeing results from early studies conducted at the French Study Bureau. In 1973, Mavic used those findings and data to produce its first glass-fiber lenticular disc wheel.

“Lenticular” refers to the lentil-like (i.e. biconvex rather than flat) shape. At the Study Bureau, Mavic engineers discovered that a lenticular-shaped wheel sliced through the air the fastest, and under some wind conditions, the lenticular flanges of the wheel could even create negative drag, increasing speed and acceleration.

“Lenticular” refers to the lentil-like (i.e. biconvex rather than flat) shape. At the Study Bureau, Mavic engineers discovered that a lenticular-shaped wheel sliced through the air the fastest, and under some wind conditions, the lenticular flanges of the wheel could even create negative drag, increasing speed and acceleration.

This new disc wheel was tested on the track and the road, but since it was against the rules at the time (unlike the first alloy rims and there’s no way to disguise the fact that it’s a disc), it was never used in a race.

Later, Mavic partnered with Gitane-Renault and the Aerotechnical Institute at the Saint-Cyr engineering school to produce the first aero road bike. The bike had modified aero tube shapes, integrated handlebars, internal cable routing, and most importantly, deep-section Mavic CXP25 alloy rims. Bernard Hinault rode the Mavic-equipped Profil aero bike to victory in four of the five individual time trials at the 1979 Tour de France, taking the final yellow jersey as well.

Then, in 1984, Mavic debuted the Comete carbon fiber disc wheel at the Tour de France. The Comete was the first commercially available disc wheel. It did away with fiberglass used in the original 1973 disc wheel but kept the revolutionary lenticular shape. The rim and hub were joined together with two specially shaped carbon discs.

Carbon disc wheels quickly became the hot new trend and professional cyclists began demanding them for prologues and time trials. Other manufacturers followed Mavic’s lead, but without aero expertise, many designed flat discs which didn't reduce drag as much as the lenticular-shaped Comete.

The following year the Comete “+ and –” appeared. This wheel had 12 cells around the edge that could hold steel weights. This allowed riders to add or remove ballast for specific events. The wheel racked up numerous wins, the most famous being Greg LeMond's final TT in the 1989 Tour de France, where he beat Laurent Fignon to the overall win by only eight seconds. In 1994, Chris Boardman used the wheel on the legendary Lotus 108 to record the fastest ever Tour de France prologue with an impressive 34.2mph average.

The following year the Comete “+ and –” appeared. This wheel had 12 cells around the edge that could hold steel weights. This allowed riders to add or remove ballast for specific events. The wheel racked up numerous wins, the most famous being Greg LeMond's final TT in the 1989 Tour de France, where he beat Laurent Fignon to the overall win by only eight seconds. In 1994, Chris Boardman used the wheel on the legendary Lotus 108 to record the fastest ever Tour de France prologue with an impressive 34.2mph average.

Mavic’s aerodynamic prowess translated well to track racing. Boardman won the 4km pursuit in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics using Mavic’s carbon tri-spoke 3G front wheel with a Comete disc rear. Four years later, Mavic introduced the iO lenticular carbon five-spoke wheel which won five medals in Atlanta.

The Comete disc, 3G, and iO have been favored by Olympic track powerhouses like Great Britain, France, and Australia. They’ve won medals in Sydney, Athens, Beijing, London, and Rio, as well as countless medals at track world championships, becoming the most successful track wheels ever produced.

A shift in performance: Tout Mavic, Zap Mavic System, and Mektronic

Though Mavic is best-known for its wheels and hubs, it dabbled in other components, including pedals, cranks, and headsets. In 1979, it made the leap to produce its first complete group, the Tout Mavic (which translates into “All Mavic”).

While providing neutral support at races, Mavic mechanics were reportedly encountering a lot of problems servicing bikes in the field. Mavic’s vice president, Art Wester, decided that they could improve on what was available and launched the Tout Mavic project with the goal of creating components that were more reliable and serviceable. The Tout Mavic rear derailleur, for example, could be rebuild with new springs, pivot pins, and bearings in a matter of minutes.

While providing neutral support at races, Mavic mechanics were reportedly encountering a lot of problems servicing bikes in the field. Mavic’s vice president, Art Wester, decided that they could improve on what was available and launched the Tout Mavic project with the goal of creating components that were more reliable and serviceable. The Tout Mavic rear derailleur, for example, could be rebuild with new springs, pivot pins, and bearings in a matter of minutes.

Sean Kelly was the first big name to achieve success on Mavic’s new group. In the spring of 1984, while riding a Tout Mavic-equipped Vitus, Kelly took victory in Paris-Nice, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, and an incredibly muddy Paris-Roubaix. That same year, he was also runner-up in Milano-Sanremo and the Ronde van Vlaanderen.

In 1989, Greg LeMond took Tout Mavic to the top step of the Tour de France, the same Tour where he used the Mavic Comete disc wheel to best Lauren Fignon in the final TT. Later that year, LeMond rode Tout Mavic to his second world championship title in Chambéry, France.

Entering the ‘90s, Mavic had bold ideas for the future of shifting. In 1992, Mavic developed an experimental, electrically-controlled derailleur which was tested in the Tour de France by the Once and RMO teams. Then in 1993, Mavic introduced the Zap Mavic System, or ZMS, the first “microprocessor driven” rear derailleur with two buttons on the handlebar that allowed riders to effortlessly change gear. This was 16 years before Shimano would release its own Dura-Ace Di2 electronic group!

Entering the ‘90s, Mavic had bold ideas for the future of shifting. In 1992, Mavic developed an experimental, electrically-controlled derailleur which was tested in the Tour de France by the Once and RMO teams. Then in 1993, Mavic introduced the Zap Mavic System, or ZMS, the first “microprocessor driven” rear derailleur with two buttons on the handlebar that allowed riders to effortlessly change gear. This was 16 years before Shimano would release its own Dura-Ace Di2 electronic group!

ZMS was beautifully simple. It didn't use electricity to actually shift. The battery sent a signal to the rear derailleur where a solenoid engaged the jockey-wheel using a horizontal pushrod. The rider’s pedaling action provided the actual energy to pull the derailleur up or down and change gear. This meant the battery was tiny and could be stored in a bar end.

ZMS gained favor among time trial specialists like Tony Rominger and Chris Boardman. Rominger felt that the faster shifting and the ability to shift without changing position provided a notable advantage. Against the advice of his team director, Rominger chose to use ZMS in the final time trial of the 1993 Tour, winning the stage and finishing second overall. Boardman used ZMS (and the Comete disc wheel) in his prologue win in the 1994 Tour de France.

ZMS was surprisingly reliable, but as is the case with many cutting-edge technologies, there were occasional teething issues. Though Rominger won the final Tour TT in 1993, he reported that the ZMS derailleur, which had worked perfectly in training, stopped functioning halfway through the stage (his team director was right!). In the Dauphine, Boardman's mechanic didn't screw the battery cap down tight enough and during the TT the spring loaded battery compartment launched the battery pack from the handle bars into the crowd. Issues like this scared most pros away and ultimately led to the demise of ZMS before it could be improved.

ZMS was surprisingly reliable, but as is the case with many cutting-edge technologies, there were occasional teething issues. Though Rominger won the final Tour TT in 1993, he reported that the ZMS derailleur, which had worked perfectly in training, stopped functioning halfway through the stage (his team director was right!). In the Dauphine, Boardman's mechanic didn't screw the battery cap down tight enough and during the TT the spring loaded battery compartment launched the battery pack from the handle bars into the crowd. Issues like this scared most pros away and ultimately led to the demise of ZMS before it could be improved.

But Mavic wasn’t done. In 1999, Mavic introduced Mektronic, the world’s first wireless electronic group. It worked much like ZMS but used digitally-coded radio waves to control shifts. Control buttons were built into the hoods and connected to onboard computer showed time, speed, distance, and sprocket positions. Again, Mavic was far ahead of the curve, releasing its wireless group 16 years before SRAM would introduce Red eTap.

Sadly, like ZMS, Mektronic would fade away before it could be refined and perfected. It had it small contingent of passionate fans, but as the decade drew to a close, corporate powers made the decision that Mavic should refocus on the root of its success: innovative wheels.

Mavic and the mountain bike

In the 1980s, Mavic took a keen interest in American BMX racing and the budding mountain bike scene in California and Colorado. Mavic realized that off-road disciplines were more than just passing fancies and moved in to support the market.

In 1983, designers at Mavic were already thinking about complete pre-built wheel systems. Over a decade before it would release the groundbreaking Cosmic and Helium road wheel system, it created the first pre-built off-road wheels, the TTM 504 20” BMX wheelset. In 1985, Mavic released its first cross-country mountain bike-specific rims: the Rando M4 and M5. Then, in 1987, Mavic provided neutral service for the Paris-Gao-Dakar mountain bike race. To commemorate the race, it released the iconic Paris Gao Dakar rims and hubs.

In 1983, designers at Mavic were already thinking about complete pre-built wheel systems. Over a decade before it would release the groundbreaking Cosmic and Helium road wheel system, it created the first pre-built off-road wheels, the TTM 504 20” BMX wheelset. In 1985, Mavic released its first cross-country mountain bike-specific rims: the Rando M4 and M5. Then, in 1987, Mavic provided neutral service for the Paris-Gao-Dakar mountain bike race. To commemorate the race, it released the iconic Paris Gao Dakar rims and hubs.

Beginning in 1994, Mavic played a major part in a downhill mountain bike arms race between Eric Barone and Christian Taillefer. Barone and Taillefer both set out to claim the downhill speed record, piloting custom aero mountain bikes down steep ski slopes in the French Alps equipped with specially made Mavic aero wheels and studded mountain bike tires.

The two traded the speed record for years, and in the end, Barone came out on top, achieving 138.752mph (223,30kph) in 2015.

The two traded the speed record for years, and in the end, Barone came out on top, achieving 138.752mph (223,30kph) in 2015.

With the game-changing, pre-built Helium road wheelset in 1996, Mavic simultaneously released the Crossmax wheelset for mountain bikes. Like the Helium, the Crossmax was a wheel system. The hubs, spokes, and rim were designed in conjunction to maximize weight savings and handling characteristics. Crossmax would make its professional debut in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics.

Mavic has continued to be a major presence in modern mountain biking. Its work on UST technology helped bring tubeless wheels and tires to mountain bikes. With racers like cross-country legend Julien Absalon, Mavic developed prototype 29” Crossmax wheels in 2011. Mavic sought to create a 29er wheel that had more stiffness and lighter weight to compete with traditional 26" wheels. The Crossmax SLR 29er was released in 2012 and helped usher in the modern 29er mountain bikes that have taken over XC racing.

The race saviors: Mavic neutral service

As I said in the introduction, my memories of the Tour de France all feature Mavic’s iconic yellow neutral service vehicles. With Mavic neutral service ending this year, I thought it fitting to close out this story by looking back at what made Mavic’s neutral service so special.

Mavic neutral service started in 1973 at Paris-Nice. Supposedly, the idea came to Mavic's then-chairman, Bruno Gormand, after he lent his car to a Directeur Sportif in the 1972 Dauphiné whose transport had broken down. Mavic’s decision to provide spare bikes and wheels to all competitors revolutionized the sport. In the days before neutral service, a broken bike often ended a rider’s race.

Mavic neutral service started in 1973 at Paris-Nice. Supposedly, the idea came to Mavic's then-chairman, Bruno Gormand, after he lent his car to a Directeur Sportif in the 1972 Dauphiné whose transport had broken down. Mavic’s decision to provide spare bikes and wheels to all competitors revolutionized the sport. In the days before neutral service, a broken bike often ended a rider’s race.

Mavic took this new job seriously. In the beginning, mechanics often took over 30 seconds to change a wheel. Mavic decided this was too long and began training its mechanics so they could change a rear wheel in 15 seconds and a front in less than 10, keeping riders in the race.

Before race radios, riders also relied on Mavic neutral service cars to relay messages and receive information regarding time gaps. They’d even provide bottles on hot days for riders who were out of water and too far from their team car.

Over the years, many pros have been saved by a Mavic car or moto providing a spare bike or wheel. I’ll never forget Stuart O'Grady in the 2007 Paris-Roubaix.

O’Grady punctured on the cobbles and fell off a breakaway group containing race favorite Tom Boonen. A Mavic moto immediately came to his aid with a wheel and he was able to join a chasing group 1:30 behind. He bridged back up to the front and then soloed away to the finish, becoming the first Australian to win Roubaix. Without neutral service, his comeback after the puncture would have been impossible.

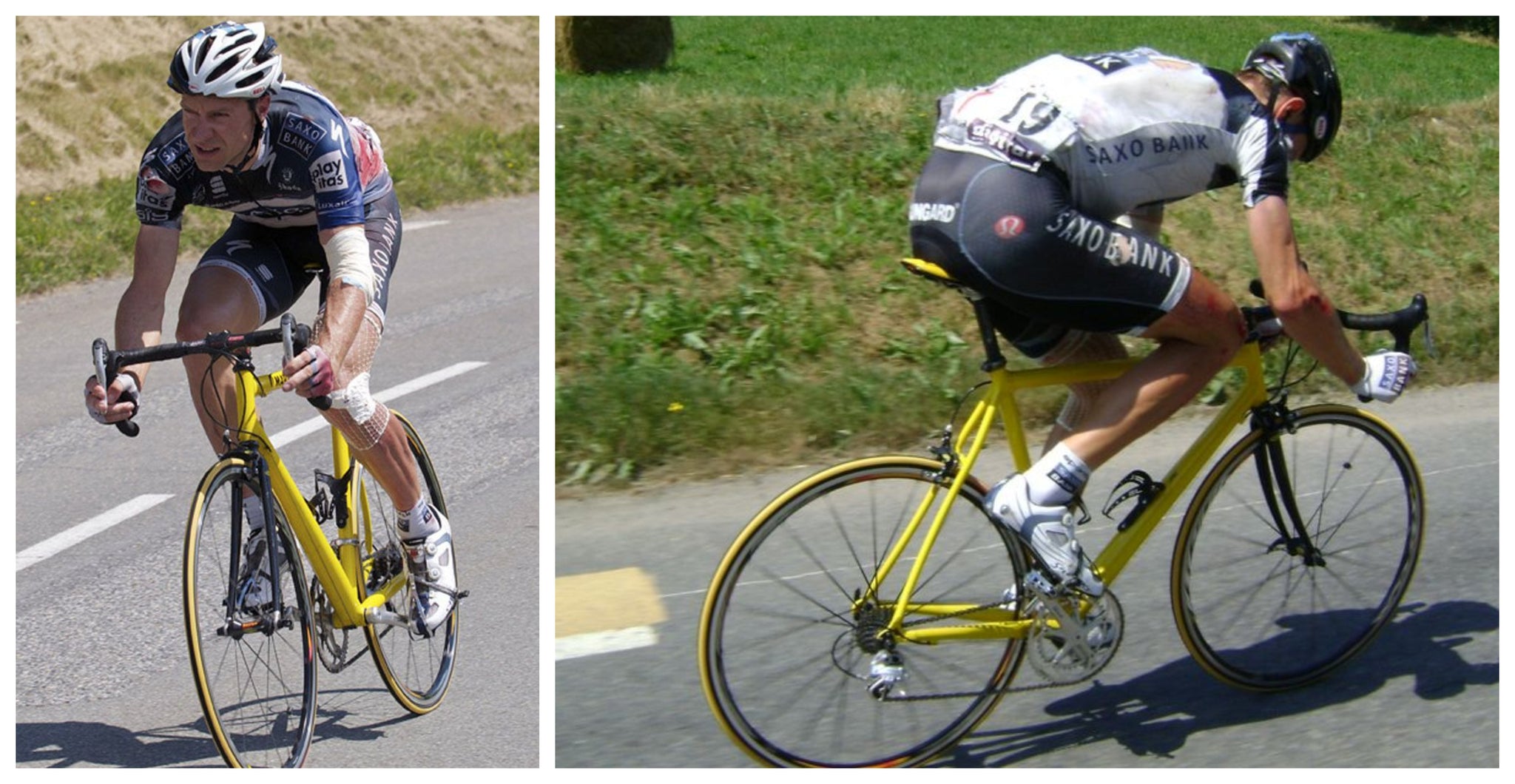

Another, more amusing story is that of Jens Voigt in the 2010 Tour de France.

Jens getting it done on a tiny neutral service bike.

Jens getting it done on a tiny neutral service bike.

On the Col de Peyresourde, Voigt crashed hard and broke the derailleur off his bike. All the team cars were up the road so he took a neutral service bike, but it was a bike from Mavic’s junior support program. It was several sizes too small and had toe clips and junior gearing. But Voigt hunched over and pedaled the comically tiny bike, determined to finish the stage after abandoning the Tour the year prior. Eventually, he found a policeman waiting with a spare bike left by his team car. The neutral service bike allowed him to complete the stage and make it to Paris with his team.

There are countless stories like these of neutral service saving riders, and there’s no telling how many riders owe their races to their presence. Though Mavic has left the neutral service game behind, it’s left its mark. Shimano’s blue neutral service cars will work just fine, but for me, they lack a certain Je ne sais quoi. I hope, one day, to see the iconic yellow Mavic cars return.

Photos courtesy of Mavic.