Sixteen hours a day of prepping, cooking, and managing an award-winning restaurant would leave most people depleted. Not Chef Matthew Accarrino.

In addition to earning 10 consecutive Michelin stars for SPQR, his restaurant in San Francisco – a star every year since 2012 – Accarrino was voted the 2014 Food & Wine “Best New Chef," and is a five-time James Beard Foundation Award nominee.

At 44, he could have opened three restaurants by now. But if he expanded his business, he couldn’t fit cycling into his life. And Accarrino needs cycling. But not because cycling brings him balance. It’s that he’s happiest when he's hurting — the harder the ride, the better.

Accarrino’s drive began almost 30 years ago, when he experienced a decidedly unwelcomed pain. Although an accident forced him to give up his teenage dream of becoming a pro cyclist, it led to the ambitious life he lives today.

[button]SHOP ALL BIKES[/button]

Cycling is one of Accarrino's lifelong passions. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

When he was 13, Accarrino was introduced to cycling by a friend’s father. It was the only sport that ever stuck, and together they rode and raced locally. Accarrino learned quickly, had natural athleticism and talent, and dreamt of becoming a pro road cyclist. But during the fall of his junior year, when he was 17, he ran and jumped to catch a Frisbee on a grassy hill behind his high school. What Accarrino didn’t know at that moment would change his life.

Accarrino was born with a benign bone tumor in his right femur. As he grew, the bone had produced a gap around the tumor; his femur was essentially hollow. When he caught the Frisbee and landed, the bone shattered upon impact. The tibia, underneath the femur, flew up into his body like a dagger, severing soft tissue. Accarrino went into shock; he didn’t feel a thing. He saw his right heel in the air pointing the wrong way. He heard people around him shouting “Oh my God," but they sounded miles away.

“Please. Please, I want my leg!”

In the ambulance, sensation finally hit – he was blinded by excruciating pain. It was so visceral and piercing that he saw red rings of light surrounded by gold. He felt nauseous. He ground his teeth and bit his lip. He struggled to slow his breathing and control the panic in his chest.

In the hospital, Accarrino heard the doctors say, “You may need to lose the leg,” before the anesthesia lulled him into sleep. “Please. Please, I want my leg,” he pleaded. And then, he was out.

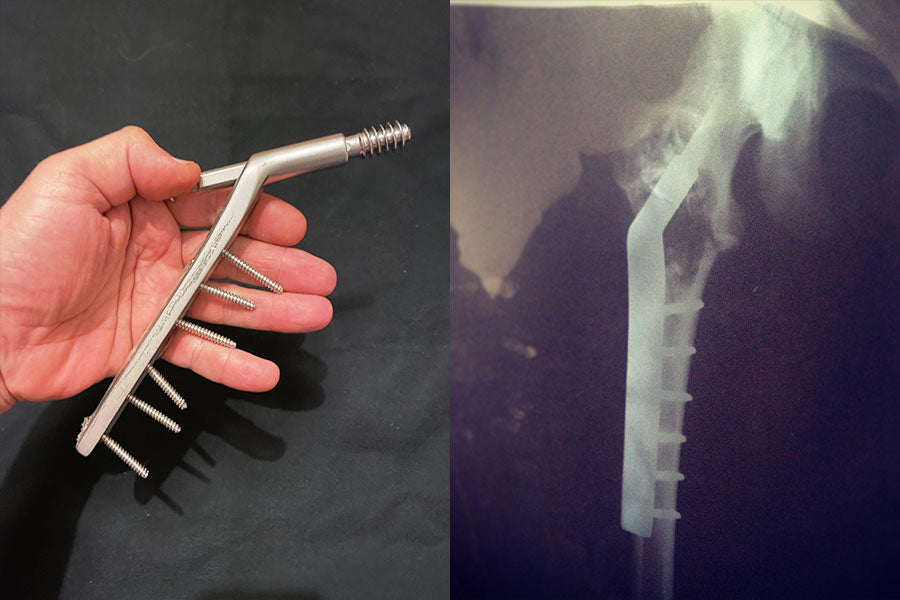

Accarrino's injury required a lot of hardware. Photo courtesy Matthew Accarrino

He underwent a nine-hour surgery, in which a pin, a plate, six screws, and an eight-inch-long titanium rod were screwed into place to mimic an intact femur bone. If that failed, they would have to amputate. Accarrino was in the ICU for two weeks, fighting for his leg.

For the next two years, he could barely walk without assistance. He spent the rest of his junior year and most of his senior year being homeschooled, and enduring countless hours of physical therapy. Dreams of racing pro had been shattered along with his leg. But something else happened during those years. He watched cooking shows – a lot of them – especially Julia Child, and discovered a new passion.

Accarrino making pasta in his San Francisco restaurant, SPQR. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

Accarrino descends from a family that cherishes good food, and the traditions and rituals that accompany cooking. His paternal grandmother, born in Puglia, Italy, always had “a big pot of tomato sauce simmering away with beef on bone, sausages, [and all the other special ingredients] in her kitchen.” He was endlessly curious about the process, and why she was using what she was using. In her kitchen, he “learned to eat pasta with the sauce and then the meat dishes after. Very Italian,” he says.

His maternal grandmother was an expert baker. “She made the best pies – especially her pecan pie,” says Accarrino. Luckily, he had the foresight to write down her pie recipe. It is a recipe he still uses today.

“I wanted to play at the top of the game and see if I could hang.”

A new dream germinated and Accarrino enrolled in Fairleigh Dickinson’s hospitality program, graduated, and went on to the prestigious Culinary Institute of America in upstate New York. While juggling a full-course load, he also worked in fine dining in Short Hills, New Jersey. There, he met his childhood inspiration, Julia Child, as a part of a dinner she cooked at a hotel. “She was and is an icon. She broke so many molds and brought people together around something they could all appreciate: good food.”

Accarrino quickly rose through the ranks, becoming one of America's best young chefs. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

After school, he plunged headfirst into his career over the next seven years. He sought challenges and pushed himself. “I wanted to play at the top of the game and see if I could hang,” he said.

"You can never exactly replicate a dish, so how can you gauge perfection? What is perfect?”

The average age for a chef du cuisine, French for “chief of the kitchen”or “head chef,” is 39. Accarrino earned the position at 24, before going on to work as part of the opening management team under Thomas Keller, the chef and owner of Per Se in New York.

He was a part of the team that opened the restaurant, which went on to win the top 30 out of 30 in the Zagat guide. Out of the 50 best restaurants in the world, Per Se was listed at number one.

Working with the best of the best and learning what it takes to create a superlative dining experience, Accarrino realized what he wanted in his own kitchen. He was surrounded by people, who, like him, never rested on a dish being good, great, or perfect. “There is no ‘perfect’ in the kitchen,” he says. You can never exactly replicate a dish, so how can you gauge perfection? What is perfect?” he says. Perfection is unattainable. “Real achievement comes from finding a new limit for yourself.”

Before he discovered a love for the kitchen, Accarrino had dreams of being a pro cyclist. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

In 2007, a girlfriend gave him a bike for his birthday. After 12 years of not riding, everything clicked; he felt 13 again. There was an instant, unmatchable elation, especially when pedaling as hard as he could. He didn’t realize how much he had missed his beloved sport.

On face value, competitive cycling and professional cooking seem incompatible. Cyclists, even amateurs, are off their feet, legs elevated, getting massages, and resting as much as possible when they’re not riding or at desk jobs. They’re in bed by 10 p.m. and up at 5 a.m. to train. Accarrino is up at 5 a.m. to train, but he’s also up until midnight, working on his feet in his restaurant and planning the next day’s menu.

Just as in the kitchen, on the bike, he continually aims to be better than he was the day before.

"When most people hit road bumps, they slow down. I floor it.”

Even at the top level of the sport, on the World Tour where the field is stacked with pros, “They aren’t really racing to beat each other,” says Accarrino. “They’re racing to best themselves.”

At 17, he learned that life could change in a split-second. So, he cooks and rides to beat himself every time. He rides so hard that when he does train with others, it's with local pros.

The roads around San Francisco are ideal for cycling, and Accarrino takes full advantage of them. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

In 2014, Accarrino began working with coaches. Not to motivate him, but to force himself to slow down and rest. For Accarrino, a slow pace – on the bike and in life – feels unnatural. “In general, I’m a person who needs to be told to ease up, not to go harder.”

“If it’s easy, it’s not worth it,” he says. “I can be pretty happy suffering. ... When most people hit road bumps, they slow down. I floor it,” says Accarrino.

Yet unlike many celebrated chefs, he’s not volatile – he’s soft spoken and maintains a calm, controlled demeanor. It’s the difference between competing with yourself and competing with others.

Intensity in the kitchen, intensity on the bike — it is Accarrino's way. Photo: Christopher Stricklen

When asked if his devotion to excellence on the bike and in his craft has come at a cost, Accarrino replies, “I resigned from being a normal human being, the favorite son, or the best partner a long time ago.” But he’s okay with that.

“When you spend a lifetime in the restaurant industry, you come to terms with the reality that, in a sense, you resign from a whole lot of [so-called] normal things: you work early and very late, sleep less, miss holidays and celebrations; there isn’t much down time,” he says. “That’s just the nature of the restaurant business.”

Ultimately, Accarino makes sacrifices in his pursuit of exceptionalism in the kitchen and on the bike. “Finding balance is as elusive as finding perfection,” he says, “but that won’t stop me from pursuing both."

What Chef Matthew Accarrino rides

Frame: Wilier Triestina Jena carbon gravel

Drivetrain: SRAM Red AXS

Cockpit: Zipp

Wheels: Zipp 202 carbon

Tires: Panaracer Gravelking

[button]SHOP WILIER TRIESTINA BIKES[/button] | [button]SHOP SRAM[/button] | [button]SHOP ZIPP[/button]